Medford Water Quality Trading Program

CASE STUDY — In 2011, Medford, Oregon, faced a problem common for cities nationwide.

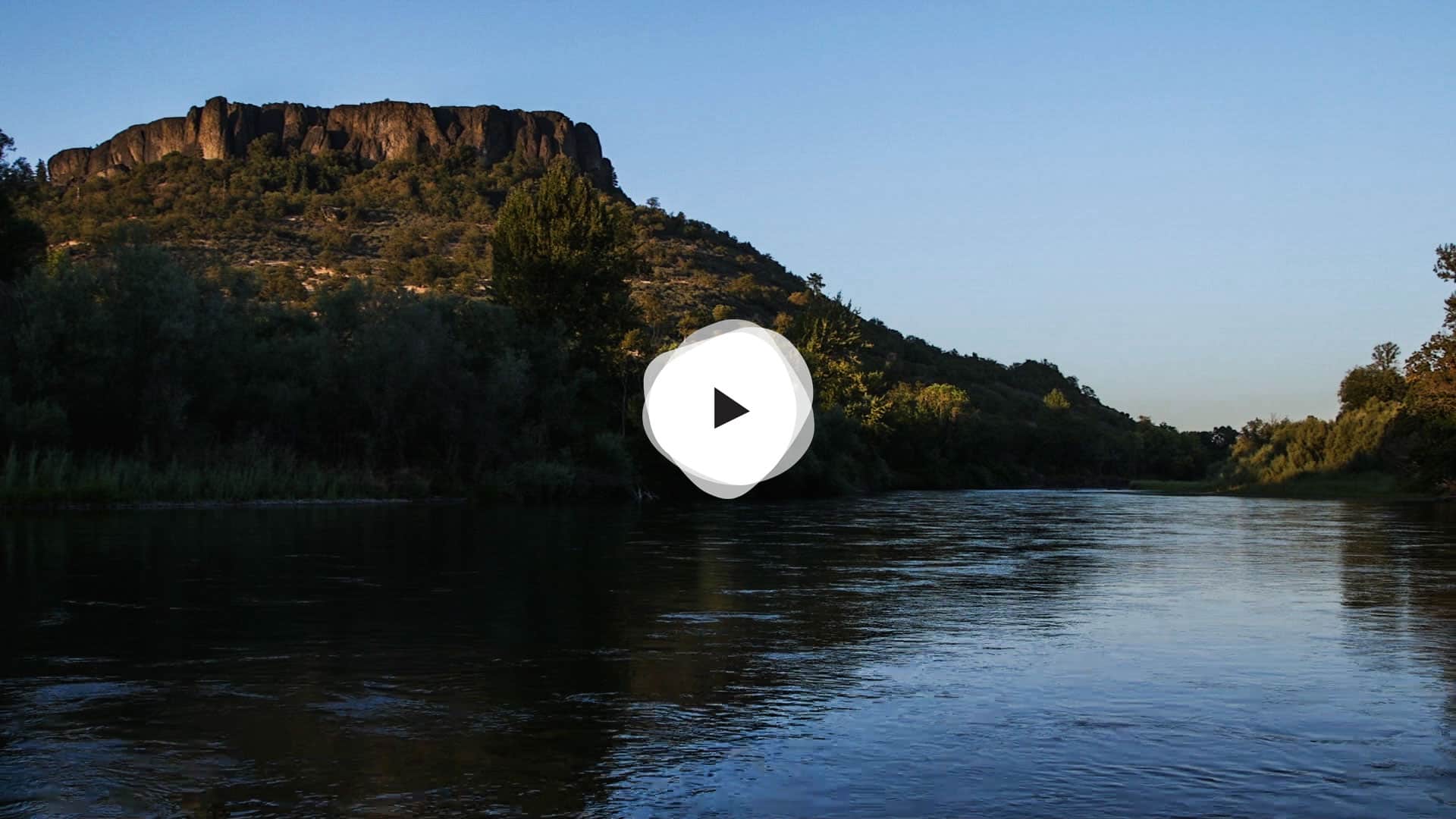

Upon treating sewage from nearly 200,000 people, the city’s wastewater treatment plant discharges an average of 17 million gallons of clean — but warm — water to the Rogue River every day.

Here’s the challenge: The historically cold Rogue River is already warming, and the water the facility is returning to the river could increase its temperature by an additional 0.18 degree Celsius.

Warmer rivers have less oxygen and cause eggs to incubate earlier, decreasing survival rates.

“Very minor temperature changes in the river can have a dramatic effect on fish populations,” said Eugene Wier, project manager with The Freshwater Trust. “The city needed to do something about that to meet its new permit requirement.”

To comply with the Clean Water Act, the city had to offset the impact of its warm-water discharge. Fortunately, there was no shortage of options in front of plant employees like Tom Suttle.

Cooling towers or chiller could be installed. Water could be held in ponds until it was at the appropriate temperature. Warm water could be reused elsewhere. The problem?

“All of those were very expensive,” said Suttle.

Tom Suttle is the Water Reclamation Division Construction Manager for the City of Medford, Oregon.

Chillers and storage lagoons can cost $15 million. Reusing water elsewhere could cost $40 million.

The Freshwater Trust offered the city something different; a solution that stood out next to the engineered proposals in terms of both dollars spent and benefits received.

The city could instead pay landowners to plant trees along their stretch of the river to shade the stream and keep the water cool.

The bill for taxpayers? Approximately $6.5 million – a more than $8 million savings.

And the benefits of those trees would extend far beyond producing shade for fish. They filter pollutants like agricultural runoff, reduce carbon in the atmosphere, and provide essential habitat for wildlife.

Approximately 32 acres or 5 miles of stream have been planted with native plants.

The proposal was accepted, and a first of its kind, regulator-approved water quality trading program was born to meet the temperature requirements. Shade generated from trees planted would be quantified and expressed as credits that the city could purchase.

“The Freshwater Trust finds the property, coordinates with the landowner, does the planting, maintains it, has it certified by a third-party certification group, and we get a certificate that a certain section of planting gives us so many kilocalories of temperature offset,” said Suttle. “We’re buying shade.”

The credits are tracked in kilocalories. A kilocalorie represents the amount of energy required to raise the temperature of a liter of water by 1.0 degree Celsius. One credit equals one kilocalorie per day.

To ensure planting would indeed mitigate the plant’s impacts on the river, trading is done at a 2 to 1 ratio. The Freshwater Trust was tasked with generating 600 million temperature credits to offset the wastewater treatment plant’s future obligation to mitigate 300 million kilocalories per day of impact on the river.

This approach to restoration is defined by The Freshwater Trust as Quantified Conservation. It’s the method of using data and technology to ensure that every restoration action taken translates to a positive outcome for the environment.

So far, 32 acres or 5 miles of stream have been planted with native plants such as Ponderosa Pine, Black Cottonwood, Big Leaf Maple, Oregon Ash and White Alder.

Leases with landowners are for 20 year periods, giving The Freshwater Trust the opportunity to maintain the project sites, ensure the native trees flourish, and keep the invasive plants at bay.

“In 20 years, these trees are going to be 80 feet tall,” said Wier. “Our goal is to have the forest of the future come up deeper, thicker, and taller to provide more and more thermal buffering to this stream.”

But The Freshwater Trust doesn’t carry out this project alone, and that means the economy benefits. It’s a collaborative effort with many local business involved.

The thousands of trees put in the ground are grown by Graig Delbol, owner of Althouse Nursery in Cave Junction, Oregon.

Graig Delbol, owner of Althouse Nursery in Cave Junction, Oregon, grows many of the trees we use in this project.

“If you’re going to have a healthy environment, you’re going to have a healthy economy,” said Delbol. “The jobs are very scarce in rural America, so we’re fortunate to be able to offer some employment out here.”

Local father and son team Dan and Dave Bish of Plant Oregon, a family owned nursey in Talent, Oregon, then step in for planting and maintaining.

“We get to be stewards of the river, and we are helping to clean the water and keep it cool,” said Dave. “We’re planting native species while clearing out invasive species. It’s really amazing to see a site transform.”

The project is a win-win for both the economy and the environment.

Many agree, including President Obama who highlighted the program during the 2012 White House Conference on Conservation.

“It worked for business; it worked for farmers; it worked for salmon,” said Obama. “Those are the kinds of ideas that we need in this country — ideas that preserve our environment, protect our bottom line, and connect more Americans to the great outdoors.”

Check out the piece in Scientific American about this program.

To learn more about solutions that benefit the environment and the economy, continue reading about our compliance solutions.

Questions about our Medford program? Contact David Primozich, Conservation Director.