Sandy River Basin: A reach restored

While our organization was founded on the banks of the Deschutes, some of our deepest restoration roots run through Oregon’s Sandy River basin.

The 500-mile system stretches between the Mt. Hood National Forest and the Portland metro area. It encompasses the Bull Run watershed, which supplies Oregon’s largest city with drinking water.

Timber harvests, removal of large instream wood to reduce flood risks, increased development, and road construction took such a toll on habitat that Sandy River salmon and steelhead were listed under the Endangered Species Act in 1998.

The threat was enough to prompt the formation of the Sandy River Basin Partners, a group of public and private organizations partnering to determine funding and strategic action. Together, The Freshwater Trust (TFT ) and others determined the Salmon River and Still Creek to be two high-priority areas. More than 100 opportunities for improving habitat for migrating fish were identified.

Since 2006, we’ve installed nearly 305 large wood structures and reactivated more than 58,000 feet of historic side channel. And over the years, our staff has witnessed exactly how that’s improved wild populations of once threatened species.

In 2016, the number of winter steelhead spawning in the upper Sandy basin had increased by more than 350% what it was when they were listed as threatened in 1998. Spring Chinook counts were also up, at 40 redds per mile. That’s more than 200% the long-term average.

TFT and the Partners estimate that all restoration opportunities identified in 1999 will be complete by 2045.

“This is perhaps the most powerful testament to our ability to make a difference for a place.”

-Mark McCollister

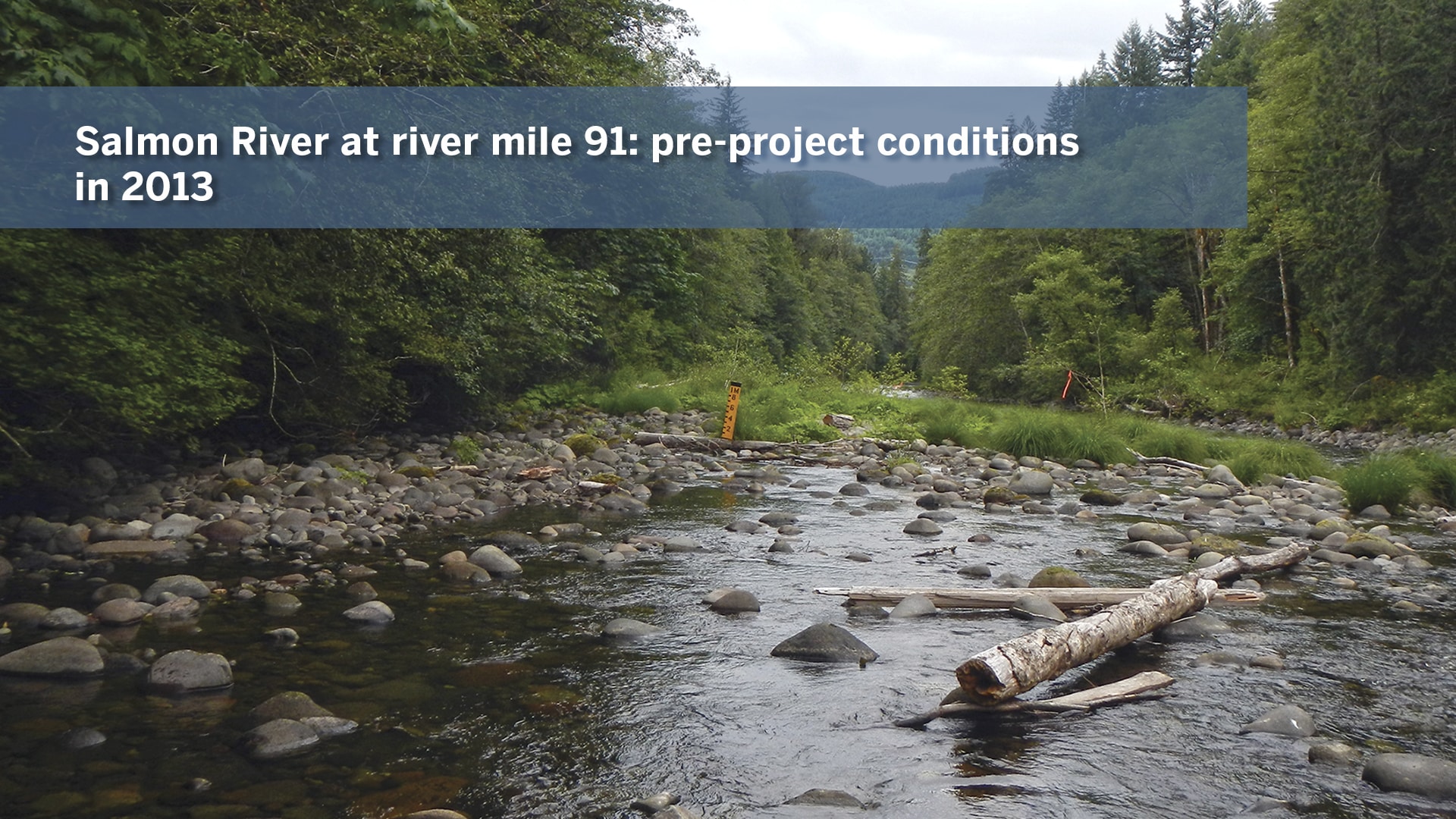

Spotlight on the Salmon River

The Salmon River winds through the Salmon-Huckleberry Wilderness, plunging over waterfalls in a narrow basalt canyon, and passing through eight miles of public and private lands before it meets the Sandy River. From headwaters to confluence, it has been dubbed “wild and scenic” by the federal government and attracts thousands of fishermen, paddlers, campers and hikers every year.

This classic Northwest beauty has many admirers. But it’s not what it used to be. Following a major flood in 1964, sections of the Salmon River were straightened and diked. Side channels were disconnected and floodplain connections were reduced as a result. Furthermore, woody debris was removed for fear it would exacerbate flooding and damage downstream infrastructure.

“The Salmon had been scraped of its ability to support the fish that once thrived here,” said Jeff Fisher, habitat monitoring coordinator. “Nearly a decade has been spent devising how to make it what it once was naturally.”

Since 2006, 3.8 miles of the Salmon River main stem has been restored. Approximately 2.2 miles of side channel has been reconnected, and 78 large wood structures have been constructed.

During a 2016 snorkel survey of a 2.5 mile reach of the Salmon River, 80% of migrating spring Chinook were holding in enhanced pools where our large wood structures were installed.

“The proof is in the presence,” said Fisher. “We continue to see a positive and immediate response from fish.”