Seeing the forests for the river

As summer reaches its peak here in the Pacific Northwest, simple things may be taken for granted:

Kids running through sprinklers. The fact that the sprinklers are on at all. The opportunity to extend your neck to a hose and drinking from cool, clean water.

Water is plentiful here, a luxury much of the West doesn’t enjoy. But while we’re often fortunate to have enough, its quality depends on a number of variables that can go unconsidered.

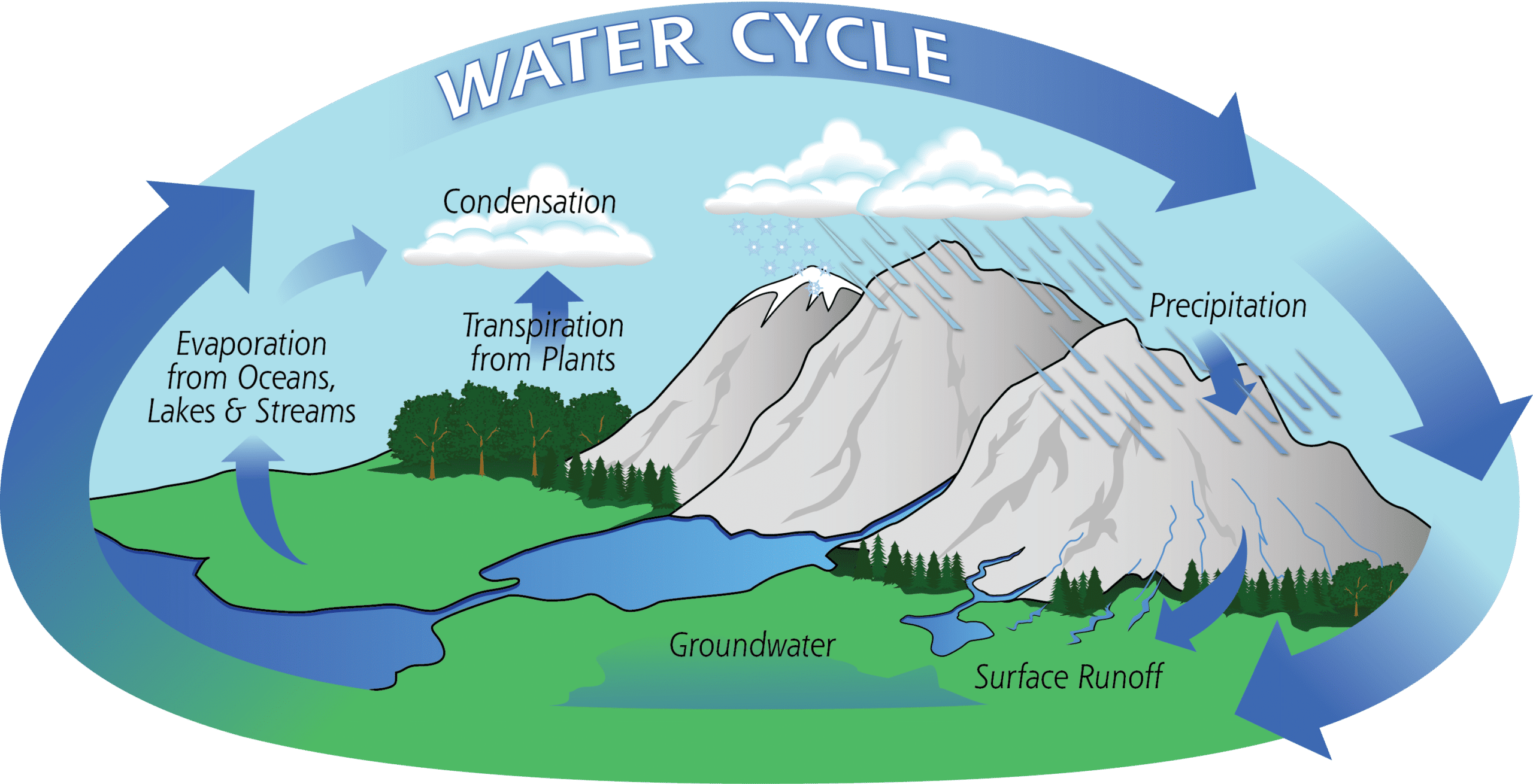

In the backs of our minds we all likely can recall a diagram like the one below. It’s a staple of science texts, imprinted somewhere along with the periodic table and the structure of an atom. Yet it doesn’t tell the full story of water. It ties together the cyclical nature of water and illustrates the relationship between oceans, mountains, clouds, rain and rivers. But it fails to explain just how critical forests are to this process and the ways activities upstream impact the quality of the water at the faucet.

Doesn’t it make sense to ask ourselves, “What’s just upstream of us? Where is this water before it enters our pipes and pumps?”

The quality of the water coming out of our taps is completely dependent upon the quality of the land and forests upstream. Connections like these are not simply lost in diagrams but in practice as well. History has shown that the intrinsic connections between natural resources has not been well understood or even ignored. Times are changing and with that comes a better understanding of our connectedness and effects of our actions. Where there are examples of damages, there are several examples of how sound management has led to the benefit of water, wildlife, and people.

GreenWood Resources, a Portland-grown timberland investment advisory and management organization and my employer (full disclosure), manages more than 150,000 acres along the coastal range of northwest Oregon and southwest Washington.

We understand that managing these lands must consider not just the production of timber products, but also the health of fish and people.

There are countless springs, creeks, streams, and rivers that don’t just provide habitat for the anadromous fish so well known in the PNW, but water for towns and cities. We often partner with municipalities, the Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board (OWEB), local watershed councils, and non-profit organizations to share the costs of restoration and conservation projects.

Take Ecola Creek, for instance. In the peak beach season of July and August, the City of Cannon Beach draws water directly from the West Fork of Ecola Creek (also known as Elk Creek) to supplement groundwater springs that serve the town year-round. All this water, even the spring water, comes from forests that GreenWood manages. During the winter and spring, the plentiful rain filters through soil layers and replenishes groundwater reservoirs, which then return to the surface as springs.

Year after year, GreenWood identifies potential projects and budgets for the removal of small culverts, replacing them with open-bottom culverts or bridges that allow better connectivity to groundwater, slow the flow to allow for better fish passage, and decrease sediment runoff caused by erosion. We engage in direct enhancement and restoration by placing large woody debris, often from our own harvests, in streams to increase complexity and provide fish habitat. Beyond what is required by regulations, we have voluntarily extended ‘no-touch buffers’ of 100 feet from the banks of Ecola Creek and its tributaries to help preserve soil structure and minimize disturbance, reducing the factors that can lead to erosion and sedimentation. The buffers also help maintain shade, which keeps the water cool for the many cold-water fish species that call this area home.

These actions go beyond what is required by the Oregon Forest Practices Act and come as direct costs to the company. Through engagement with the local community, and through understanding the connections between proper stewardship and water quality, we design management plans that address a variety of issues. Many of our staff and contractors live in the area and benefit directly, but more than that, we see this type of management as contributing to the greater good of the ecosystem – it is the right thing to do.

And the results have been quantified. Salmonid abundance on some restored creeks in the area has improved tenfold.

In 2016, Cannon Beach put out an Annual Water Quality Report stating that the water quality “meets or exceeds all State and Federal standards.”

Beyond the numbers, it is about what’s seen with your own eyes. You can stand in the shade on the banks of these streams and see the water pouring over and around logs and the dorsal fins of Coho during spawning season.

Greenwood Resources has long been a supporter of The Freshwater Trust, mainly because we agree with their thesis that working lands and healthy rivers can coexist. In fact, we both believe they must.

###

Belton Copp is a Portfolio Manager at GreenWood Resources and an inaugural member of the Headwaters Council at The Freshwater Trust. He has worked around the county on stream and meadow restoration on grazing lands, in wetlands mitigation, and as a fly fishing guide. Prior to moving to Oregon, Belton earned a Masters in Environmental Management from the Nicholas School at Duke and an MBA from UNC Kenan-Flagler.

Enjoying Streamside?

This is a space of insight and commentary on how people, business, data and technology shape and impact the world of water. Subscribe and stay up-to-date.

Subscribe- Year in Review: 2023 Highlights

By Ben Wyatt - Report: Leveraging Analytics & Funding for Restoration

By Joe Whitworth - Report: Transparency & Transformational Change

By Joe Whitworth - On-the-Ground Action – Made Possible By You

By Haley Walker - A Report Representing Momentum

By Joe Whitworth