Streamside Forest Pilot Celebrates 10 Years, Anchors Restoration

March 1, 2022

There will always be a special place in a carpenter’s heart for their first house. A chef’s first mastered recipe. An inventor’s prototype. A business’s first dollar.

These are foundational things – beginnings to build upon.

Ten years ago, The Freshwater Trust (TFT) broke ground on its first fish habitat project in the Rogue River basin. In the Denman Wildlife Area, a refuge area near White City, Oregon, TFT and its partners planted more than 6,000 native trees and shrubs along Little Butte Creek, a 17-mile tributary of the Rogue.

The project was the organization’s entry into Water Quality Trading, a regulatory mechanism using nature to keep municipalities in compliance with the Clean Water Act – while delivering many other ancillary environmental benefits.

Water Quality Trading (WQT) is used to improve water quality and control pollutants from multiple sources. The new trees and shrubs at Denman blocked quantified amounts of solar load. Those amounts were turned into credits – shade credits – bought through this innovative ecosystem services pilot sponsored by Willamette Partnership to model a “pay for outcomes” approach to conservation investing.

The restoration project at Denman was the first project that demonstrated the approach later taken in TFT’s WQT programs with the City of Medford, the City of Ashland and the Eugene-Springfield Metropolitan Wastewater Management Commission.

Nature isn’t typically used to offset this type of impact and keep cities in compliance with the Clean Water Act. Major infrastructure, such as chillers and cooling towers at wastewater treatment plants, are traditional solutions, but they’re much more expensive for taxpayers than planting projects.

Nature was too risky, many said.

Innovation requires risk, we replied.

Last year, TFT met the first goal of its WQT program with the City of Medford: Plant enough restoration projects throughout the entire basin to offset the City’s 600 million kilocalories of solar load. By that time, other nearby cities, like Ashland, had signed on to the solution, too. Our robust, precedent-setting program, and the basis for all TFT’s revegetation work, started with a leap of faith 10 years ago in a rather unassuming public wildlife area that had once been a place for testing bombs and other artillery.

“Denman was our proof of concept,” said Olivia Duren, restoration program manager. “Water Quality Trading can be esoteric. It’s really hard to wrap your head around on paper. Denman showed how this was a real solution with real habitat benefits that could be used to comply with federal and state requirements.”

This proof-of-concept project also just happened to benefit the best salmon-producing creek in the basin.

“Every fish that passes through the creek passes by this project,” said Eugene Wier, restoration project manager and resident of the Rogue basin. “They’re now traveling through good habitat to get to more good habitat.”

TFT’s plantings built upon restoration work already happening in the refuge. Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, the Geos Institute, and OWEB had been working to restore the creek’s sinuosity after being straightened 60 to 70 years ago. TFT played an important role complementing instream improvements with robust streamside revegetation.

“This was our first crack at leveraging different projects happening by different entities on a creek at one time – something that is now a pillar of our work,” said Wier. “It was also where we formed relationships with local businesses that have been as lasting as the project itself.”

The native cottonwood, willows, ash, alders, and shrubs that TFT and small business partner Plant Oregon put into the ground a decade ago have since transformed the landscape. Today, the majority of the trees are between 3 and 7 feet tall. Over the next decade, many will grow to their maximum height of 25 feet. Some, like Black Cottonwoods, could reach over 100 feet.

Year 0: Planting native plants along the streambank at Little Butte Creek

Year 10: Those small saplings have grown and are casting shade

In addition to shading rivers, streamside forests protect water quality and provide animals with a source of food and cover. The root structures and canopies of native plants support water infiltration and retention while protecting the aquatic ecosystem from turbidity and excessive nutrient runoff resulting from erosion and high rain events. Once downed, large trees become incorporated into the river where their interaction with stream flow encourages pool development, channel complexity and recruitment of substrate, all beneficial to the four types of salmon and steelhead in the Rogue.

“It now feels like, and looks like, the natural streamside forest that has always been there,” said Duren. “The whole refuge is an oasis in an environment that can otherwise be pretty arid and harsh.”

But like any first of a kind, there was a learning curve. The refuge is just that to the four-legged and the finned. And to the two-legged as well. A few years back, a man burnt some of the plants to clear the area and deconstructed a large wood structure to begin building a cabin.

This was an exception, however. Most of the visitors walk directly through the site using a designated trail and now can hardly tell the difference between the restoration and the rest of the refuge.

“We are learning how to restore ecosystem function within the context of our communities,” said Wier.

In addition to human impact, TFT tested and learned about many things that now make its dozens of projects successful – irrigation types, flood risk management, diversity and density of plants, wildlife management and importantly, the benefits of long-term monitoring and stewardship of a project – a differentiator for TFT.

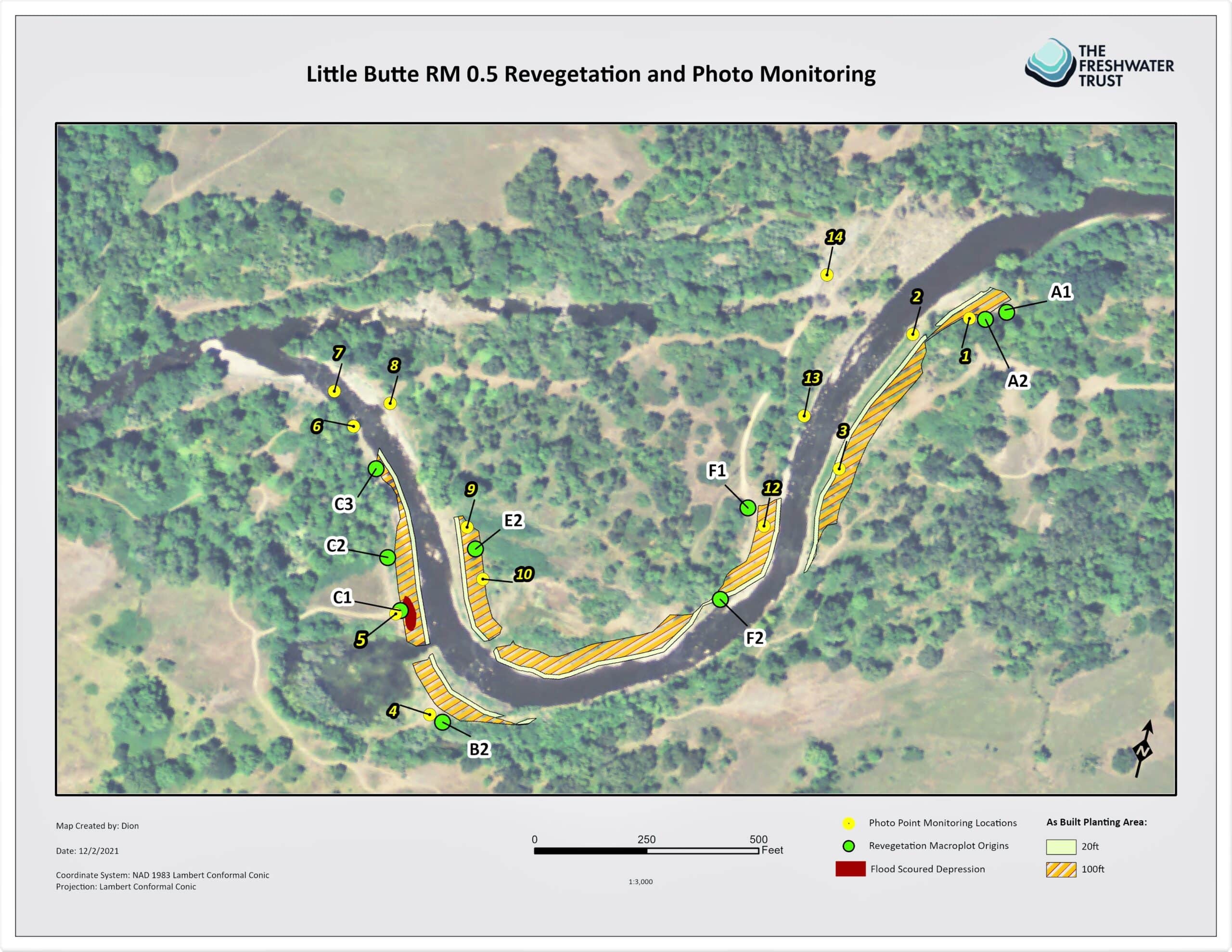

Established points for repeat photos allow a streamside forest to be monitored year after year.

“Many of our projects are monitored for 20 years, if not longer,” said Duren. “This is what allows us to ensure their durability and deliver the type of quantified outcomes that are essential for compliance obligations. We also get to see their habitat and community benefits grow as the forests do.”

From a few acres of public land, TFT grew what is now a $25 million, basin-wide restoration program.

Nearly 90,000 native trees and shrubs have since been planted along other parts of Little Butte Creek, additional tributaries, and the mainstem Rogue, generating shade and preventing nutrient runoff.

The local restoration economy has grown alongside the program, and invaluable partnerships have been formed with municipalities, agencies, landowners and small businesses. And TFT has installed nearly 150 large wood structures in key places throughout the basin where fish will use and need them the most, like in Little Butte Creek.

“This first project was a learning lab,” said Wier. “And a lot has come of that learning since.”

#ecosystem services #Little Butte Creek #Rogue River Basin #water quality trading